“They read from the book, from the Law of God, clearly, and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading” (Nehemiah 8:8).

Untangling many complex and interwoven knots is not an easy task. When faced with such a challenge, the way forward is to systematically, carefully, and patiently undo one knot at a time. That is what I hope to do in this short article.

Truth is what Christians are all about, and truth about language is no less important than the truth about the Bible, which uses language. It is my uncontroversial claim that “firmament” didn’t always mean “firmament.” Well, that’s obvious enough, since every word now in use didn’t exist before it was coined.

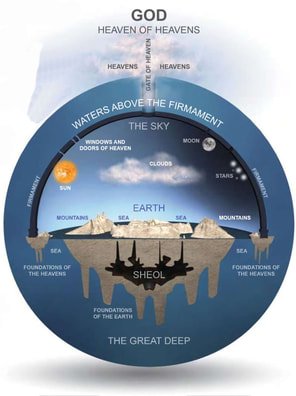

If you ask a liberal biblical scholar what the Hebrew word “רקיע” (raqia) in Genesis 1:6 means, they’ll tell you that it means “firmament.” At this point, you will ask what “firmament” means, and your scholar will go on to explain that a “firmament” is the ancient Hebrew idea of the structure of the sky, specifically, the idea that the sky is a solid dome, rising up on all sides from its base (that is, the entire earth itself) with “foundations” or “pillars” under the ground, holding the whole thing up.

For those unfamiliar with the concept, think snow globe, but the snowflakes are the sun, moon, and stars, and they’re all fixed near the top of the globe. And the ground beneath the whole dome is flat. That’s what the unbelieving scholars will tell you. And that’s also what a segment of Christians are now starting to adopt, assuming that these assumptions about Genesis, unaware of their dubious origins, truly teach. Where did these scholars get this idea and why are some believing Christians adopting it today? The factors could be multiplied (ENDNOTE 1), but let’s keep it as simple as possible for now. Let’s move into what may be more controversial, but shouldn’t be.

It’s my strong temptation to say that “firmament” isn’t a word at all because that would capture the essence of what I want to say, but it would be a little misleading. Allow me to not mislead you, but rather explain what I mean. When the King James Version translators translated רקיע (raqia) into English, they translated it as “firmament.” Good and well enough, at least in 1611. So why has that led to all this confusion today? The English word “firmament” was not originally a translation of the Hebrew word רקיע, at least not first of all. First of all, the English word “firmament” is a transliteration from the Latin word “firmamentum.” How big is the difference between a translation and a transliteration? Huge. To put it (hopefully) simply, a translation tries to take one word in one language, and understand the basic meaning of that word, and then find whatever word in a new language fits exactly or most closely with the meaning in the original language, and then use that new word in that new language. The fancy term for the language you’re starting with is called the “source language,” and the term for the language you’re translating into is called the “target language.”

So, translating a word from a source language into a target language would be something like saying “casa” if someone asked you what the Spanish word for “house” was. Now, transliteration is not the same as translation. A transliteration takes a word in the source language (let’s imagine our source language was Latin and our word was firmamentum) and puts that word into the target language, not by translating it with an equivalent word from the target language, but by taking the sounds and letters, and by matching the sounds and letters in the new, target language.

So, the English “firmament” isn’t a translation of the Latin “firmamentum,” but rather a transliteration of “firmamentum.” To give another biblical example, we Christians often use the word “Paraclete” to refer to the Holy Spirit. But the word “Paraclete” isn’t an English translation of a Greek word, but a transliteration from the Greek word “παράκλητος” (par’akletos). We took the sound of the Greek word parakletos and smoothed those sounds over into English letters to come up with the English transliterated word “paraclete.” Okay, now we have our linguistics lesson out of the way. Back to the translation(?) of the word “firmament.”

Back in 1611 when the King James Version was translated into English, there was an English word “firmament” that, at the time, simply meant “sky.” And so, following the basic use of the words as they were at the time, the KJV translators translated “רקיע” as “firmament,” knowing that every English speaker four hundred years ago would’ve understood “firmament” as “sky,” and that’s that. “Not so fast,” you might say. “If the English word ‘firmament’ meant only sky four hundred years ago, then why are all the broadcasts from trusted sources telling me that it meant ‘dome’ along with an entire cosmology that the ancient Jews had?” Good question. But before we answer that, we’ll have to back up one more time. As mentioned above, the English word “firmament” was originally a transliteration from the Latin word “firmamentum.” Now, what did firmamentum mean? Knowing what the Latin originally meant will help us understand the following:

Why the early church father Jerome translated the Hebrew רקיע as “firmamentum” when he did his work on the Latin translation of the Bible, the Latin Vulgate.

Why the KJV translators picked up on “firmamentum” when translating the Bible into English.

“Words only ever mean one thing at a time, depending on how they are used (usage) and the context they appear in (context).”

The word “firmamentum” in Latin originally meant “sky.” Yes, as a verb it also meant “to support” or “to uphold,” and sometimes even that verb meaning was used as a noun to mean “a support,” but here’s the thing. Words only ever mean one thing at a time, depending on how they are used (usage) and the context they appear in (context). When English speakers of old referred to that thing above us with the term “firmament,” they were using one definition of it at a time, the single one they were using according to what they meant by what they said (intent of the author) and according to what everyone else at the time understood it to mean (context and usage). So, as a noun, “firmamentum” meant “sky.” “Sky” is the English translation of the Latin “firmamentum,” whereas “firmament” is the English transliteration of the Latin firmamentum (for difference between translation and transliteration, see above).

Now, the English word “firmament” (which came into Middle English around 1250-1300 AD) used to be (and in some cases still is) merely a synonym for “sky,” and nothing more. The English word “firmament” meant sky, since the word it was transliterated from, “firmamentum” also meant sky. The host of forces that have combined so as to teach that “firmament” in English means this whole, strange cosmology that was apparently assumed in the Old Testament is beyond the scope of this article, but for a first shot at an explanation, see the first footnote above, as well as Vern Poythress’ masterful, biblical, and thorough work, Interpreting Eden: A Guide to Faithfully Reading and Understanding Genesis 1-3. In terms of what’s been one of the recent major arguments used to support “firmament” to mean one piece of the whole of biblical cosmology, let’s look at the most obvious linguistic reason why this is so.

Too often, Christians think in terms of surface, rather than substance. If we could move beyond the surface to the real thing, the real issue underneath, then our discussions would be much more fruitful, and we wouldn’t talk past each other so much. When you say something enough times, and you hear it often enough, then you start to really believe that that thing truly is what it sounds like. This is one of the major problems with our sound byte culture and one of the major reasons also why the left has been so successful in manipulating how words and phrases sound rather than what they really mean. Pro-choice. Pro-love. Pro-equality. Who’s against any of that? We automatically recognize the obviousness of the bait-and-switch going on here. So why do we settle for the surface instead of the substance in other worldview issues? These things should not be so, my brothers. Sadly, this is how Christians have all too often treated words and what words mean today, albeit in different contexts. Jesus told us, assuming we’d apply the truth behind his words to all the situations in life, “Do not judge by appearances, but judge with right judgment” (John 7:24). Let’s look lastly at how this easily overlooked principle has been likewise overlooked in the firmament discussion.

When you hear someone say the word “firmament” out loud, what does it sound like? Well, it sounds like something that’s firm. And if the last part of the word, “-ment,” which generally means “thing” comes right after “firm,” then wouldn’t “firmament” naturally mean “something that is hard; something that is firm”? Pair this with the older meaning of “firmament” as “sky”, and voilà! Firmament would come to mean something like “something that is hard, firm, specifically, the sky,” right? It might be easy to think so.

Etymology is the study of the original meanings of words, and the original meanings of each part of a word which makes up the whole. Many people assume that if you know where a word came from, you have better insight into what that word really means, because it’s a deeper bit of knowledge that few people are aware of. But are our assumptions about the goodness of etymology truly good things? Sadly, no. There are very many “word study fallacies” and “etymological fallacies” which are mistakes people make, thinking they’re getting to the real truth of the matter about a word by understanding what that same word used to mean. As much as I would love to cover every word fallacy in depth, that’ll have to wait for another time. Think of the word “butterfly.” The technical definition of “butterfly” is “any of numerous diurnal insects of the order Lepidoptera, characterized by clubbed antennae, a slender body, and large, broad, often conspicuously marked wings.”

If we thought we didn’t know what “butterfly” really meant, then our temptation might be to look at the etymology of the word, in order to uncover its *real* meaning. So, let’s do that, and break up “butterfly” into its individual parts, see what each part means, so that we can have a deeper understanding of the word itself. The definition of “butter” is “the fatty portion of milk, separating as a soft whitish or yellowish solid when milk or cream is agitated or churned.” And the definition for (the noun, not the verb) “fly” is, “any of numerous two-winged insects of the order Diptera, especially of the family Muscidae, as the common housefly.”

Aha! Now we really know what a butterfly is! Even more, we can see from the definition of butterfly that it is an insect from the order “Lepidoptera” and a fly is an insect from the order “Diptera!” Is this not irrefutable proof that the real meaning of a butterfly is “an insect composed from the fatty portion of milk which originally came from the insect order Diptera?” No, my friends. We can at once see how silly it is to understand the “true” definition of “butterfly” as a combination of the meanings of “butter” and “fly.” It might not be as obviously silly in other examples, but from this, we should see and recognize that words have meaning, not according to what they used to mean, and not according to the original meaning of their individual parts, but according to the word as it is used in the time it was used in by the people who used it.

The meaning of words is derived from how words are used by those who use them and from the contexts in which they were used. If we want to know what a word meant four hundred years ago, we have to look at how it was used at that time, by the speakers of the language back then. This is another reason why context is so important. We cannot have an idea about what a word means, and then inject our idea back into how those words were used decades ago and centuries ago. A few short decades ago, “gay” meant “happy,” and “nice” in the Middle English of 1250-1300AD meant “foolish or stupid.” If you used the word “gay” to mean “happy,” and “nice” to mean “foolish and stupid,” without telling anyone today what you actually mean, you will not be understood, because that’s not what those words mean today, because they’re not presently used that way (Exegetical Fallacies by D.A. Carson, Ch. 1, Word Study Fallacies).

Language is an important thing. It’s easy to mess up, as is every other area of life. But as Christians, we are commanded by God to represent the truth as it is and not how we wish it to be. Let’s represent words and meaning as they really are, and so please the God who first spoke creation into existence, and who spoke the gospel of his Son into our ears and hearts to take us from the kingdom of darkness and lies to the kingdom of light and truth under the reign of the Messiah. To close, I want to share something I had written a little while ago when pondering some things about truth, meaning, and worldview. The tone is a little different, but I hope it may be of benefit to you.

Changing, adjusting, or adding to one’s point of reference doesn’t change the truth, it merely pulls back another layer of obscurity previously unknown to us or awakens us to see that our initial frame of reference was altogether broken and in need of total replacement. What we claim about anything is only as valid as our points of reference about anything. If our point or points of reference are skewed, they must be replaced or re-adjusted according to surer ones, and ultimately, according to the most sure one - God’s Word. We must think God’s thoughts after Him, and although we must begin with our own perspective when approaching anything whatsoever, our perspective is not infallible, let alone is our perspective the ultimate, omniperspective that God Himself has of all things. And we must avail ourselves of the means God has given us to see things as clearly as we possibly can through His gifts of both general revelation (e.g. human language) and special revelation (Scripture).

ENDNOTE 1:

Many factors contribute to the concept of the “firmament” as it is popularly understood among liberal scholars and theologians and more recently, certain pockets of conservative, believing Christians. Vern Poythress writes, “Greek astronomy developed a theory of heavenly spheres from the fourth century BC onward. Over time, educated people in the Alexandrian Empire and later the Roman Empire were influenced by this theory. Moreover, the translations of the Hebrew רקיע (raq’ia; “expanse”) with στερέωμα (ster’eoma; “solid body”) in Greek and firmamentum in Latin might encourage the idea of identifying the “firmament” as a solid sphere, corresponding to one of the Greek astronomical spheres.

Ancient church interpreters could also be biased if they wanted Genesis 1 to “measure up” to the more technical knowledge represented by Greek astronomy, and so the temptation would arise to interpret Genesis 1 with a more technical and physicalistic slant than what the original Hebrew called for” (Interpreting Eden, 174, footnote 7). There are also a host of word-study fallacies that have led to the belief that Moses was teaching a physicalistic structure of the earth, and that that structure had to do with a strange, anachronistic cosmology, but fleshing each of those out exceeds the limits of this article. And, most importantly, these factors do not overturn the simple truth of the matter.

Sources (in order of importance; I drew heavily from #1 and also #2)

Interpreting Eden: A Guide to Faithfully Reading and Understanding Genesis 1-3 by Vern Poythress

Exegetical Fallacies by D. A. Carson

Biblical Words and Their Meaning by Moises Silva

Authorized: the Use and Misuse of the King James Bible by Mark Ward

The Semantics of Biblical Language by James Barr

PARTNER WITH US

It is our greatest hope and deepest prayer before God that through the ministry of Cultish, and our partnership with you, we may see God rescue countless people from darkness.